Most of the rest were medium metabolizers, and they got a negligible performance boost. Roughly half the people in the study were fast caffeine metabolizers, and they got a big performance boost from caffeine in a 10K cycling trial. Back in 2018, I wrote about a study linking the effects of caffeine to a gene that affects caffeine metabolism. To me, the strongest evidence that coffee might have some positive effects independent of caffeine comes from a different line of research. The review takes an exhaustive dive into what these various substances might do for performance, listing their “neuromuscular, antioxidant, endocrine, cognitive, and metabolic effects,” but actual evidence of a performance boost is very thin on the ground. The case in favor of coffee is based on all its other bioactive ingredients: most prominently polyphenols like chlorogenic acid that may influence blood flow and glucose levels, but also various minerals, melanoidins produced in the roasting process that have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, and small amounts of carbohydrate, protein, and fat. That wasn’t a statistically significant difference, but is it possible that coffee itself has performance benefits independent of its caffeine content? Decaf was 0.6 percent faster than placebo.

If anything, the results of that 2018 study raise the opposite question. Other studies have also found performance boosts from coffee, at least when taken in quantities that provide a known and sufficient dose of caffeine. This 2018 study, for example, found that coffee boosted one-mile run time by 1.9 percent compared to a placebo, and by 1.3 percent compared to decaffeinated coffee. To be fair, subsequent research has mostly suggested that coffee works just as well as caffeine.

Since caffeine levels were identical in the coffee and the decaf-plus-caffeine-pill trials, that suggests that something in the coffee-perhaps chlorogenic acid, one of coffee’s key antioxidant compounds-was interfering with the performance boost of caffeine. In a half-hour running test, performance was only increased with water-with-caffeine-capsule trial. The main source of that concern is a 1998 study that compared performance under five different conditions: water with placebo capsule, water with caffeine capsule, decaffeinated coffee, decaffeinated coffee with caffeine capsule, and regular coffee. That’s a lot of coffee-and caffeine from coffee appears to be absorbed more quickly than from capsules, which means you might want to finish downing all that liquid less than an hour before competition.Ī further problem is that some of the other substances in coffee might interfere with the action of caffeine. For a typical medium-roast coffee, that works out to two to four cups (16 to 32 ounces), depending on body size. Sports scientists typically recommend taking between 3 and 6 milligrams per kilogram of bodyweight an hour before competition.

One study that tested a variety of store-bought espressos found caffeine levels ranging from 51 milligrams per serving at Starbucks to 322 milligrams per serving at Patisserie Francois.Įven if you stick with a consistent source of coffee with a known amount of caffeine, getting in the optimal performance-boosting dose might be a challenge. It depends on what kind of beans you’re using, how they’re prepared, how big your cup is, and so on. The most obvious problem is that it’s hard to know exactly how much caffeine you’re getting in a cup of coffee. You can make a reasonable argument that coffee is less effective than caffeine as a performance aid.

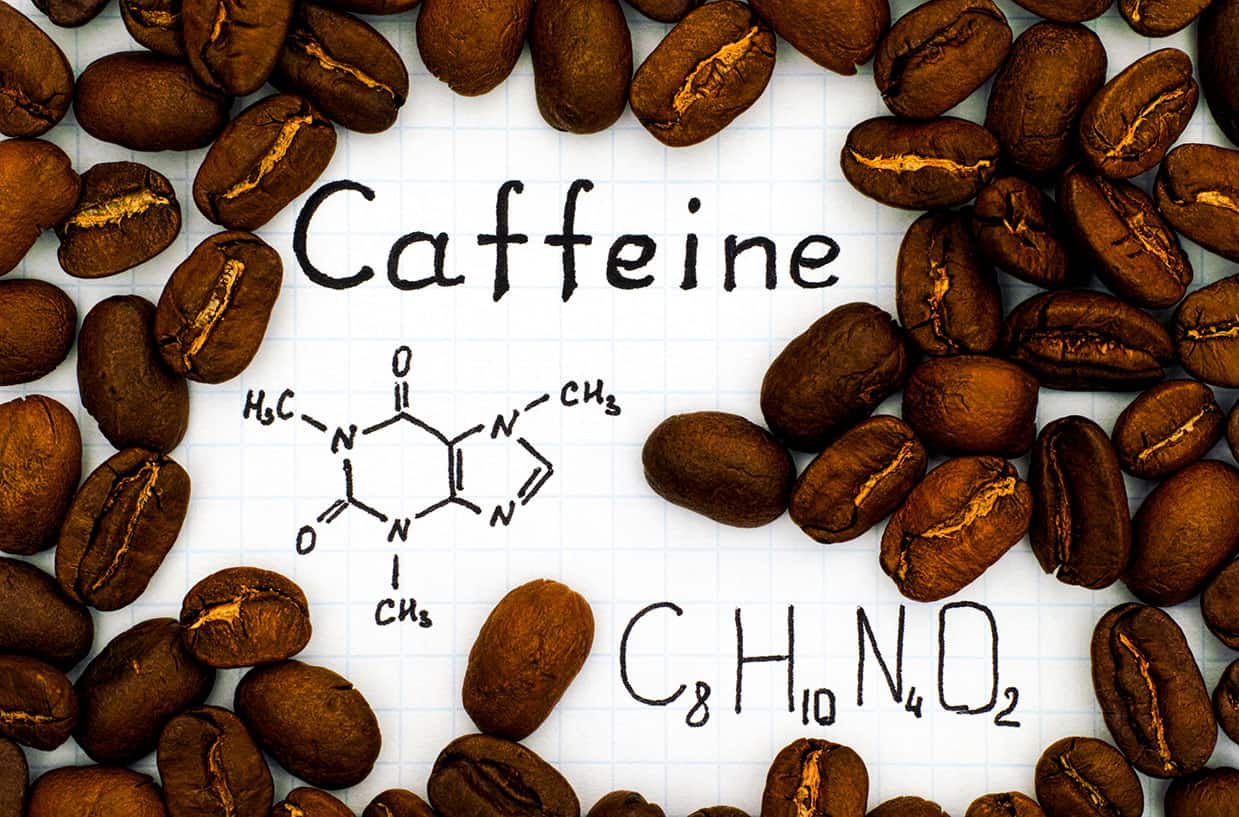

The new review, from a group of researchers led by Lonnie Lowery of Walsh University, asks whether coffee-“a complex matrix of hundreds of compounds”-provides the same athletic benefits as an equivalent dose of caffeine, or whether there are additional pros and cons. In contrast, many of my running friends swear by their pre-workout or pre-race coffee. I’ve written many, many articles about research into caffeine’s performance-boosting powers, almost all of which uses pills to provide a carefully controlled dose of caffeine. Coffee, as a new review paper in the Journal of International Society of Sports Nutrition points out, is not just liquid caffeine. Frankly, I’m surprised that the number wasn’t higher, given how effective caffeine is as a performance booster and how widespread coffee consumption is more generally.īut I’m conflating two different things. Overall, 76 percent of the samples contained caffeine, with the highest concentrations found in cycling, track and field, and rowing. A few years ago, researchers in Spain combed through the results of more than 7,000 urine samples tested for doping at competitions in various Olympic sports.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)